What people believe to be true is often as important as reality. It may, in fact, be part of the truth. – Gary Roberts, Historian

Available from these booksellers

Cold fury overtook the desperate teen. The drunken bully’s insulting words cut him like a knife—like the deadly pocketknife now clutched in his slender, shaking fist.

Once, twice, three times he struck. Bystanders gasped as blood-red smears covered his finally still hand, but the hulking blacksmith who had accosted his beloved mother uttered not a sound as he slipped slowly to the rough plank floor.

It was done.

The cheerful, friendly boy, courteous to women, kind to children, helpful to his teacher, had become a desperate criminal, an outcast.

Billy had killed his first man.

Or had he?

Controversy and conjecture surround this supposed incident, as well as almost every other aspect of the birth, life, death, age, and even the name of a young outlaw sometimes called William Bonney. Substantiated information about this villain, or hero, of the Wild West remains rare. Historical facts—as elusive as quicksilver—rapidly devolve into myth and legend. Historical writer Fredrick Nolan once noted, “Few American lives have more successfully resisted research than that of Billy the Kid.”

Most of Billy’s well known exploits—some of which actually happened—took place in New Mexico Territory, from the early 1870s until his death here in 1881.

First settled by Spanish Conquistadors around 1598—if you ignore the Native American population, which historians usually have—New Mexico entered history as the northernmost territory of Spain in the New World, the most isolated and backward of all its holdings.

The colony’s capital of Santa Fe, a meager cluster of adobe—that is, dried mud—buildings, populated mainly by failed adventurers and refugees from the Inquisition, stood surrounded by scattered but peaceful Pueblo villages. Attackers, in the form of nomadic Navajos, Apaches, and Utes, always posed a threat, however. The fledgling settlement maintained its only contact with other Europeans by mule-back or ox-cart over the Camino Real to Mexico City, 1200 miles to the south.

When Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, Nuevo Mexico became the most isolated and backward province of this new country. The year 1821 also marked the opening of the Santa Fe Trail. Now, regular contact with the growing United States could begin, as Franklin, Missouri, waited a mere 900 miles to the east.

Finally, following our 1848 war with Mexico, New Mexico Territory—still accessible mainly over the by-now-well-traveled Santa Fe Trail—took its place as an isolated and backward part of the United States. In this new American Territory, public education was unknown, English was a foreign language, and telegraph wires had yet to make an appearance.

Change came slowly. Billy the Kid himself witnessed the beginnings of New Mexico’s first real emergence from isolation when the railroad arrived in 1878. Still, most Americans continued to consider this part of the United States to be primitive and otherwise undesirable for years to come. Susan Wallace, wife of New Mexico Governor Lew Wallace, and clearly not a fan of the place, wrote in 1879, “We should have another war with Old Mexico to make her take back New Mexico.”

This backward and isolated state of affairs certainly contributed to our lack of documented information about Billy the Kid. Record keeping took low priority on a frontier where the struggle for survival loomed daily and illiteracy rates ran high. A mysterious fire destroyed New Mexico’s store of public records in 1892, creating even more gaps.

When facts are scarce, legends grow. They certainly did in Santa Fe, with the popular frontier pastime of storytelling filling in many of those gaps with hearsay and myth.

In spite of difficulties in documentation, we can be reasonably sure Billy Bonney spent fair amounts of time in Santa Fe on at least two occasions. How do we know? Billy’s reminiscing friends, along with early journalists who followed his escapades, and his numerous biographers all tell us so, even if official records cannot.

Local folks spinning their tales of real—or wished-for—celebrity encounters might be expected to make up stories. Therefore, we usually look to professional journalists and skilled biographers for accurate information about a historical figure.

In Billy’s case, this is not necessarily a good idea. Much of what we long accepted as fact has come to be recognized as fantasy in the last few decades.

Accuracy rarely struck early writers as an important goal. Frontier journalists often emerge as demonstrably misleading, frequently influenced by political agendas or the need to sell newspapers.

Billy’s first biographers turn out to be even less reliable. They readily invented events to flesh out gaps in their knowledge, or to present themselves in a more favorable light. This was especially true of Billy’s primary biographer, Pat Garrett, who himself played a leading role in the activities he recorded in his seminal 1882 work, The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid.

Later, noted cowboy and Pinkerton detective Charles Siringo followed Garrett’s lead—repeating earlier misinformation and making up a little of his own—to create his 1920 bestseller, History of “Billy the Kid.”

Chicago journalist Walter Noble Burns then borrowed from both works, added stories from others who had known Billy, and produced his wildly popular but highly fictionalized 1926 biography, The Saga of Billy the Kid. His efforts established Billy as a lasting romantic hero.

For years, we merely accepted what had come before. If you can’t trust Sheriff Pat Garrett, who can you trust? As it turns out, Garrett, aided by his ghostwriter, Ash Upson, was one of Billy’s least trustworthy historians.

So, as researchers have delved into the accuracy of accepted beliefs, new information has emerged, much of it contradictory both to earlier reports and to findings of other modern investigators. Perhaps that’s what makes Billy such a fascinating character. We can each pick and choose from a myriad of “facts” to create our own special Billy the Kid.

Nevertheless, Billy did spend time in Santa Fe on two—or possibly three—occasions.

Why does this matter? Why do we care?

From the standpoint of today’s visitor exploring enchanting and enchanted quirks of The City Different, Billy’s time in Santa Fe adds one more intriguing twist to four centuries of history, myth, and mystery enshrined in its adobe walls.

Professional and amateur historians trying to uncover the real person that was Billy the Kid recognize other reasons to care. This future desperado first came to New Mexico’s capital as a boy of twelve or thirteen. Surely, Santa Fe’s frontier character and Hispanic culture helped shape the personality of the newly arrived youth.

Did Kit Carson’s tales of daring whet Billy’s appetite for adventure? Did the boy from “back East” hone his quick wit and lively sense of humor trading quips with saloon patrons as he sang for tips around the Plaza? Did the future monte dealer develop his card-playing skills by sneaking into infamous Palace Avenue gambling dens? Did casual violence of life at the End of the Santa Fe Trail desensitize the impressionable youngster to later killing?

And where did Billy acquire his love and respect for Hispanic culture? He spent much of his later life working, playing, courting, and hiding within Hispanic communities in southeastern New Mexico. There, he became a beloved hero. Billy’s fluent Spanish and charming manners made El Chivito a welcome guest in Hispanic rancheros and sheep camps.

Perhaps Billy learned his fluent Spanish playing in Santa Fe streets with youthful descendants of its Conquistadors. Maybe the young teen acquired his gallant manners and his taste for lovely señoritas attending bailes and fandangos at la fonda, the Inn at the End of the Santa Fe Trail.

And what about the citizenry Billy the Kid met during his first stay in Santa Fe? Did the charming young teen encounter any of Santa Fe’s older residents who would later figure significantly in his brief life?

Did he gawk in awe at the nearly seven-foot-tall veteran lawyer who had once gotten away with killing a Chief Justice of the Territorial Supreme Court in the billiards room of la fonda, but would later prosecute Billy for murder?

Did the spirited youngster encounter the sober state legislator, busily writing New Mexico’s first public education law, whom he would eventually ambush from behind an adobe wall in a little town far from the ancient capital?

Did he notice a newly appointed judge as they passed each other on the street, “a meek little man with a bald head and a frightened look in his eyes,” who would one day sentence Billy to hang for that infamous deed?

Moreover, what was Santa Fe itself like in 1873? How were its last days as the rip-roaring End of the Santa Fe Trail playing out during Billy’s first exposure to this outpost of the Wild West?

“Civilization,” in the form of Americanization, was starting to take hold in the traditionally Hispanic capital when Billy first arrived. What changes were already taking place as Taos mountain men and Philadelphia photographers, Mexican ricos and Hopi traders, pioneer homesteaders and fancy ladies, Jewish merchants and French-born priests, Missouri bull skinners and Irish nuns, Anglo cavalrymen and Hispanic politicos all exchanged pleasantries around the Plaza?

How did these characters of Santa Fe—and Santa Fe’s own character—contribute to the development of a desperado? Can we, and even should we, sort facts from legends as they swirl around one young resident—later known as Billy the Kid—as we try to understand the intricate mosaic that is our American heritage?

This selection comes from Billy the Kid in Santa Fe, Book One: Young Billy

Available from these booksellers

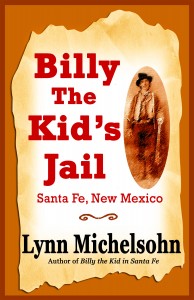

You might also enjoy this brief book about the jail that successfully held Billy the Kid for three months.

Paperback US $7.95

Available from these booksellers

© Cleanan Press, Inc. 2004 – 2014